Organ (music)

Organ (music)

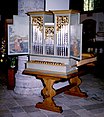

Organ in church | |

| Classification | Keyboard instrument |

|---|---|

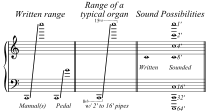

| Playing range | |

| Related instruments | |

| see Keyboard instrument | |

| Musicians | |

| see List of organists | |

| Builders | |

| see Category:Organ builders | |

| More articles or information | |

In music, the organ is a keyboard instrument of one or more pipe divisions or other means for producing tones, each played with its own keyboard, played either with the hands on a keyboard or with the feet using pedals.

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The organ is a relatively old musical instrument,[1] dating from the time of Ctesibius of Alexandria (285–222 BC), who invented the water organ. It was played throughout the Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman world, particularly during races and games.[2] During the early medieval period it spread from the Byzantine Empire, where it continued to be used in secular (non-religious) and imperial court music, to Western Europe, where it gradually assumed a prominent place in the liturgy of the Catholic Church.[2] Subsequently, it re-emerged as a secular and recital instrument in the Classical music tradition.

Overview[edit]

Pipe organs use air moving through pipes to produce sounds. Since the 16th century, pipe organs have used various materials for pipes, which can vary widely in timbre and volume. Increasingly hybrid organs are appearing in which pipes are augmented with electric additions. Great economies of space and cost are possible especially when the lowest (and largest) of the pipes can be replaced.

Non-piped organs include:

- pump organs, named also reed organs or harmoniums, which like the accordion and harmonica (or "mouth organ") use air to excite free reeds;

- electronic organs (both analog and digital), notably the Hammond organ, which generate electronically produced sound through one or more loudspeakers.

Mechanical organs include the barrel organ, water organ, and Orchestrion. These are controlled by mechanical means such as pinned barrels or book music. Little barrel organs dispense with the hands of an organist and bigger organs are powered in most cases by an organ grinder or today by other means such as an electric motor.

Pipe organs[edit]

The pipe organ is the largest musical instrument. These instruments vary greatly in size, ranging from a cubic meter to a height reaching five floors,[4] and are built in churches, synagogues, concert halls, and homes. Small organs are called "positive" (easily placed in different locations) or "portative" (small enough to carry while playing).

The pipes are divided into ranks and controlled by the use of hand stops and combination pistons. Although the keyboard is not expressive as on a piano and does not affect dynamics (it is binary; pressing a key only turns the sound on or off), some divisions may be enclosed in a swell box, allowing the dynamics to be controlled by shutters. Some organs are totally enclosed, meaning that all the divisions can be controlled by one set of shutters. Some special registers with free reed pipes are expressive.

It has existed in its current form since the 14th century, though similar designs were common in the Eastern Mediterranean from the early Byzantine period (from the 4th century AD) and precursors, such as the hydraulic organ, have been found dating to the late Hellenistic period (1st century BC). Along with the clock, it was considered one of the most complex human-made mechanical creations before the Industrial Revolution. Pipe organs range in size from a single short keyboard to huge instruments with over 10,000 pipes. A large modern organ typically has three or four keyboards (manuals) with five octaves (61 notes) each, and a two-and-a-half octave (32-note) pedal board.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart called the organ the "King of instruments".[5] Some of the biggest instruments have 64-foot pipes (a foot here means "sonic-foot", a measure quite close to the English measurement unit)[citation needed] and it sounds to an 8 Hz frequency fundamental tone. Perhaps the most distinctive feature is the ability to range from the slightest sound to the most powerful, plein-jeu impressive sonic discharge, which can be sustained in time indefinitely by the organist. For instance, the Wanamaker organ, located in Philadelphia, USA, has sonic resources comparable with three simultaneous symphony orchestras. Another interesting feature lies in its intrinsic "polyphony" approach: each set of pipes can be played simultaneously with others, and the sounds mixed and interspersed in the environment, not in the instrument itself.

Church[edit]

Most organs in Europe, the Americas, and Australasia can be found in Christian churches.

The introduction of church organs is traditionally attributed to Pope Vitalian in the 7th century.[citation needed] Due to its simultaneous ability to provide a musical foundation below the vocal register, support in the vocal register, and increased brightness above the vocal register, the organ is ideally suited to accompany human voices, whether a congregation, a choir, or a cantor or soloist.

Most services also include solo organ repertoire for independent performance rather than by way of accompaniment, often as a prelude at the beginning the service and a postlude at the conclusion of the service.

Today this organ may be a pipe organ (see above), a digital or electronic organ that generates the sound with digital signal processing (DSP) chips, or a combination of pipes and electronics. It may be called a church organ or classical organ to differentiate it from the theatre organ, which is a different style of instrument. However, as classical organ repertoire was developed for the pipe organ and in turn influenced its development, the line between a church and a concert organ became harder to draw.

Concert hall[edit]

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, symphonic organs flourished in secular venues in the United States and the United Kingdom, designed to replace symphony orchestras by playing transcriptions of orchestral pieces. Symphonic and orchestral organs largely fell out of favor as the orgelbewegung (organ reform movement) took hold in the middle of the 20th century, and organ builders began to look to historical models for inspiration in constructing new instruments. Today, modern builders construct organs in a variety of styles for both secular and sacred applications.

Theatre and cinema[edit]

The theatre organ or cinema organ was designed to accompany silent movies. Like a symphonic organ, it is made to replace an orchestra. However, it includes many more gadgets, such as mechanical percussion accessories and other imitative sounds useful in creating movie sound accompaniments such as auto horns, doorbells, and bird whistles. It typically features the Tibia pipe family as its foundation stops and the regular use of a tremulant possessing a depth greater than that on a classical organ.

Theatre organs tend not to take nearly as much space as standard organs, relying on extension (sometimes called unification) and higher wind pressures to produce a greater variety of tone and larger volume of sound from fewer pipes. Unification gives a smaller instrument the capability of a much larger one, and works well for monophonic styles of playing (chordal, or chords with solo voice). The sound is, however, thicker and more homogeneous than a classically designed organ.

In the USA the American Theater Organ Society (ATOS) has been instrumental in programs to preserve examples of such instruments.

Chamber organ[edit]

A chamber organ is a small pipe organ, often with only one manual, and sometimes without separate pedal pipes that is placed in a small room, that this diminutive organ can fill with sound. It is often confined to chamber organ repertoire, as often the organs have too few voice capabilities to rival the grand pipe organs in the performance of the classics. The sound and touch are unique to the instrument, sounding nothing like a large organ with few stops drawn out, but rather much more intimate. They are usually tracker instruments, although the modern builders are often building electropneumatic chamber organs.

Pre-Beethoven keyboard music may usually be as easily played on a chamber organ as on a piano or harpsichord, and a chamber organ is sometimes preferable to a harpsichord for continuo playing as it is more suitable for producing a sustained tone.

Non-piped organs[edit]

Reed or pump organ[edit]

The pump organ, reed organ or harmonium, was the other main type of organ before the development of the electronic organ. It generated its sounds using reeds similar to those of an accordion. Smaller, cheaper and more portable than the corresponding pipe instrument, these were widely used in smaller churches and in private homes, but their volume and tonal range was extremely limited. They were generally limited to one or two manuals; they seldom had a pedalboard.

- Harmonium or parlor organ: a reed instrument, usually with several stops and two foot-operated bellows.

- American reed organ: similar to the Harmonium, but that works on negative pressure, sucking air through the reeds.

- Melodeon: a reed instrument with an air reservoir and a foot-operated bellows. It was popular in the US in the mid-19th century. (This should not to be confused with the diatonic button accordion which is also known as the melodeon.)

The chord organ was invented by Laurens Hammond in 1950.[6] It provided chord buttons for the left hand, similar to an accordion. Other reed organ manufacturers have also produced chord organs, most notably Magnus from 1958 to the late 1970s.[7]

Electronic organs[edit]

Since the 1930s, pipeless electric instruments have been available to produce similar sounds and perform similar roles to pipe organs. Many of these have been bought both by houses of worship and other potential pipe organ customers, and also by many musicians both professional and amateur for whom a pipe organ would not be a possibility. Far smaller and cheaper to buy than a corresponding pipe instrument, and in many cases portable, they have taken organ music into private homes and into dance bands and other new environments, and have almost completely replaced the reed organ.

- Hammond

The Hammond organ was the first successful electric organ, released in the 1930s. It used mechanical, rotating tonewheels to produce the sound waveforms. Its system of drawbars allowed for setting volumes for specific sounds, and it provided vibrato-like effects. The drawbars allow the player to choose volume levels. By emphasizing certain harmonics from the overtone series, desired sounds (such as 'brass' or 'string') can be imitated. Generally, the older Hammond drawbar organs had only preamplifiers and were connected to an external, amplified speaker. The Leslie speaker, which rotates to create a distinctive tremolo, became the most popular.

Though originally produced to replace organs in the church, the Hammond organ, especially the model B-3, became popular in jazz, particularly soul jazz, and in gospel music. Since these were the roots of rock and roll, the Hammond organ became a part of the rock and roll sound. It was widely used in rock and popular music during the 1960s and 1970s by bands like Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Procol Harum, Santana and Deep Purple. Its popularity resurged in pop music around 2000, in part due to the availability of clonewheel organs that were light enough for one person to carry.

- Allen

In contrast to Hammond's electro-mechanical design, Allen Organ Company introduced the first totally electronic organ in 1938, based on the stable oscillator designed and patented by the Company's founder, Jerome Markowitz.[8] Allen continued to advance analog tone generation through the 1960s with additional patents.[9] In 1971, in collaboration with North American Rockwell,[10] Allen introduced the world's first commercially available digital musical instrument. The first Allen Digital Organ is now in the Smithsonian Institution.[11]

- Other analogue electronic

Frequency divider organs used oscillators instead of mechanical parts to make sound. These were even cheaper and more portable than the Hammond. They featured an ability to bend pitches.

In the 1940s until the 1970s, small organs were sold that simplified traditional organ stops. These instruments can be considered the predecessor to modern portable keyboards, as they included one-touch chords, rhythm and accompaniment devices, and other electronically assisted gadgets. Lowrey was the leading manufacturer of this type of organs in the smaller (spinet) instruments.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a type of simple, portable electronic organ called the combo organ was popular, especially with pop, Ska (in the late 1970s and early 1980s) and rock bands, and was a signature sound in the pop music of the period, such as The Doors and Iron Butterfly. The most popular combo organs were manufactured by Farfisa and Vox.

Conn-Selmer and Rodgers, dominant in the market for larger instruments, also made electronic organs that used separate oscillators for each note rather than frequency dividers, giving them a richer sound, closer to a pipe organ, due to the slight imperfections in tuning.

Hybrids, starting in the early 20th century,[12] incorporate a few ranks of pipes to produce some sounds, and use electronic circuits or digital samples for other sounds and to resolve borrowing collisions. Major manufacturers include Allen, Walker, Compton, Wicks, Marshall & Ogletree, Phoenix, Makin Organs, Wyvern Organs and Rodgers.

- Digital

The development of the integrated circuit enabled another revolution in electronic keyboard instruments. Digital organs sold since the 1970s utilize additive synthesis, then sampling technology (1980s) and physical modelling synthesis (1990s) are also utilized to produce the sound.

Virtual pipe organs use MIDI to access samples of real pipe organs stored on a computer, as opposed to digital organs that use DSP and processor hardware inside a console to produce the sounds or deliver the sound samples. Touch screen monitors allows the user to control the virtual organ console; a traditional console and its physical stop and coupler controls is not required. In such a basic form, a virtual organ can be obtained at a much lower cost than other digital classical organs.

Other organ types[edit]

Mechanical[edit]

- Barrel organ—made famous by organ grinders in its portable form, the larger form often equipped with keyboards for human performance

- Organette—small, accordion-like instrument manufactured in New York in the late 1800s

- Novelty instruments or various types that operate on the same principles:

Orchestrion, fairground organ (or band organ in the USA), dutch street organ and Dance organ—these pipe organs use a piano roll player or other mechanical means instead of a keyboard to play a prepared song.

Steam[edit]

The wind can also be created by using pressurized steam instead of air. The steam organ, or calliope, was invented in the United States in the 19th century. Calliopes usually have very loud and clean sound. Calliopes are used as outdoors instruments, and many have been built on wheeled platforms.

Organ music[edit]

Classical music[edit]

The organ has had an important place in classical music, particularly since the 16th century. Spain's Antonio de Cabezón, the Netherlands' Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, and Italy's Girolamo Frescobaldi were three of the most important organist-composers before 1650. Influenced in part by Sweelinck and Frescobaldi, the North German school rose from the mid-17th century onwards to great prominence, with leading members of this school having included Buxtehude, Franz Tunder, Georg Böhm, Georg Philipp Telemann, and above all Johann Sebastian Bach, whose contributions to organ music continue to reign supreme.

During this time, the French Classical school also flourished. François Couperin, Nicolas Lebègue, André Raison, and Nicolas de Grigny were French organist-composers of the period. Bach knew Grigny's organ output well, and admired it. In England, Handel was famous for his organ-playing no less than for his composing; several of his organ concertos, intended for his own use, are still frequently performed.

After Bach's death in 1750, the organ's prominence gradually shrank, as the instrument itself increasingly lost ground to the piano. Nevertheless, Felix Mendelssohn, César Franck, and the less famous A.P.F. Boëly (all of whom were themselves expert organists) led, independently of one another, a resurgence of valuable organ writing during the 19th century. This resurgence, much of it informed by Bach's example, achieved particularly impressive things in France (even though Franck himself was of Belgian birth). Major names in French Romantic organ composition are Charles-Marie Widor, Louis Vierne, Alexandre Guilmant, Charles Tournemire, and Eugène Gigout. Of these, Vierne and Tournemire were Franck pupils.

In Germany, Max Reger (late 19th century) owes much to the harmonic daring of Liszt (himself an organ composer) and of Wagner. Paul Hindemith produced three organ sonatas and several works combining organ with chamber groups. Sigfrid Karg-Elert specialized in smaller organ pieces, mostly chorale-preludes.

Among French organist-composers, Marcel Dupré, Maurice Duruflé, Olivier Messiaen and Jean Langlais made significant contributions to the 20th-century organ repertoire. Organ was also used a lot for improvisation,[13] with organists such as Charles Tournemire, Marcel Dupré, Pierre Cochereau, Pierre Pincemaille and Thierry Escaich.

Some composers incorporated the instrument in symphonic works for its dramatic effect, notably Mahler, Holst, Elgar, Scriabin, Respighi, and Richard Strauss. Saint-Saëns's Organ Symphony employs the organ more as an equitable orchestral instrument than for purely dramatic effect. Poulenc wrote the sole organ concerto since Handel's to have achieved mainstream popularity.

Because the organ has both manuals and pedals, organ music has come to be notated on three staves. The music played on the manuals is laid out like music for other keyboard instruments on the top two staves, and the music for the pedals is notated on the third stave or sometimes, to save space, added to the bottom of the second stave as was the early practice. To aid the eye in reading three staves at once, the bar lines are broken between the lowest two staves; the brace surrounds only the upper two staves. Because music racks are often built quite low to preserve sightlines over the console, organ music is usually published in oblong or landscape format.

Jazz[edit]

Electronic organs and electromechanical organs such as the Hammond organ have an established role in a number of popular-music genres, such as blues, jazz, gospel, and 1960s and 1970s rock music. Electronic and electromechanical organs were originally designed as lower-cost substitutes for pipe organs. Despite this intended role as a sacred music instrument, electronic and electromechanical organs' distinctive tone-often modified with electronic effects such as vibrato, rotating Leslie speakers, and overdrive-became an important part of the sound of popular music.

The electric organ, especially the Hammond B-3, has occupied a significant role in jazz ever since Jimmy Smith made it popular in the 1950s. It can function as a replacement for both piano and bass in the standard jazz combo. The Hammond organ is the centrepiece of the organ trio, a small ensemble which typically includes an organist (playing melodies, chords and basslines), a drummer and a third instrumentalist (either jazz guitar or saxophone). In the 2000s, many performers use electronic or digital organs, called clonewheel organs, as they are much lighter and easier to transport than the heavy, bulky B-3.

Popular music[edit]

Performers of 20th century popular organ music include William Rowland who composed "Piano Rags"; George Wright (1920–1998) and Virgil Fox (1912–1980), who bridged both the classical and religious areas of music.

Rock music[edit]

Church-style pipe organs are sometimes used in rock music. Examples include Tangerine Dream, Rick Wakeman (with Yes and solo), Keith Emerson (with The Nice and Emerson, Lake and Palmer), George Duke (with Frank Zappa), Dennis DeYoung (with Styx), Arcade Fire, Muse, Roger Hodgson (formerly of Supertramp), Natalie Merchant (with 10,000 Maniacs), Billy Preston and Iron Butterfly.

Artists using the Hammond organ include Bob Dylan, Counting Crows, Pink Floyd, Hootie & the Blowfish, Sheryl Crow, Vulfpeck, Sly Stone and Deep Purple.

Soap operas[edit]

From their creation on radio in the 1930s to the times of television in the early 1970s soap operas incorporated organ music in the background of scenes and in their opening and closing theme music. In the early 1970s the organ was phased out in favour of more dramatic, full-blown orchestras, which in turn were replaced with more modern pop-style compositions.

In sport[edit]

In the United States and Canada, organ music is commonly associated with several sports, most notably baseball, basketball, and ice hockey.

The baseball organ has been referred to as "an accessory to the overall auditory experience of the ballpark."[citation needed] The first team to introduce an organ was the Chicago Cubs, who put an organ in Wrigley Field as an experiment in 1941 for two games. Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, hired baseball's first full-time organist, Gladys Goodding. Over the years, many ballparks caught on to the trend, and many organists became well-known and associated with their parks or signature tunes.

Historical instruments[edit]

| (after the 16th century)[14] | |||

Predecessors[edit]

- Panpipes, pan flute, syrinx, and nai, etc., are considered as ancestor of the pipe organ.

- Aulos, an ancient double reed instrument with two pipes, is the origin of the word Hydr-aulis (water-aerophone).

Early organs[edit]

- 3rd century BC - the Hydraulis, ancient Greek water-powered organ played by valves.[15]

- 1st century (at least) - the Ptera and the Pteron, ancient Roman organ similar in appearance to the portative organs[16]

- 2nd century - the Magrepha, ancient Hebrew organ of ten pipes played by a keyboard[17][18][19]

- 8th century - Pippin's organ of 757 (Carolingian dynasty) was sent as a gift to the West by the Byzantine emperor Constantine V[20]

- 9th century - the automatic flute player (and possibly automatic hydropowered organ), a mechanical organ by the Banū Mūsā brothers[citation needed]

Medieval organs[edit]

- Portative organ: a small portable medieval instrument

- Positive organ: a somewhat larger though still portable instrument

- Regal: a portable late-medieval instrument with reed pipes and bellows; forerunner of the harmonium and reed organ

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The organ developed from older musical instruments like the panpipe, therefore is not the oldest musical instrument.

- ^ a b Douglas Bush and Richard Kassel eds., "The Organ, an Encyclopedia." Routledge. 2006. p. 327.

- ^ Ring, Trudy (1994), International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa, 4, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 1884964036

- ^ The Wanamaker Organ is built from the 2nd to 7th floors.

- ^ The King of Instruments - National Catholic Register

- ^ Laurens Hammond, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2009 - His later inventions included the chord organ (1950, i.e. Hammond S-6 chord organ).

- ^ "'Play by Numbers' Organ Hottest Musical Merchandise". Billboard. May 11, 1959. p. 1.

- ^ "Low frequency oscillator". Patents.google.com. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Search Patents - Justia Patents Search". Patents.justia.com. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Allen Organ collaborative effort with North American Rockwell". Allenorgan.com. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Congressional Record Extensions of Remarks Articles". Congress.gov. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Synthetic Radio Organ Church Diagram French Print 1934, The ILlustration Newspaper of 1934, Paris

- ^ Szostak, Michał (1 September 2018). "Instrument as a source of inspiration for the performer". The Organ. Musical Opinion Ltd. 386: 6–27. ISSN 0030-4883.

- ^ "Landkreis Bad Kreuznach - Regal (1988, Gebr Oberlinger) - Copy of an instrument by Michael Klotz, ca. 1600". Kreis-badkreuznach.de. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Untitled Document". Web.archive.org. 5 October 2006. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Greek and Roman Pipe Organs Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Bellum Catiline - two items from "The Story of the Organ" by C. F. Abdy Williams, published in 1903 by Walter Scott Publishing.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Hunt 2008

- ^ Barnes 2007

- ^ Williams, Peter F. (1993). The Organ in Western Culture, 750-1250. p. 137ff

References[edit]

- Barnes, William Harrison (2007). The Contemporary American Organ - Its Evolution, Design And Construction. Barnes Press. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-4067-6023-1.

- Hunt, Henry George Bonavia (2008). A Concise History of Music. BiblioLife. p. 137. ISBN 978-0554753874.

Further reading[edit]

- Choosing a Church Organ in the 21st Century

- Rimbault, Edward Francis (c. 1865). . London: William Reeves.

External links[edit]

- Organ Library of the Boston Chapter, AGO. 45,000 items of organ music.

- Music and organ recital at Notre-Dame de Paris

- npor.org.uk – Homepage of the National Pipe Organ Register of the British Institute of Organ Studies, with extensive information on and many audio samples of original instruments

- The Organ Historical Society – The Society promotes a widespread musical and historical interest in American organbuilding through collection, preservation, and publication of historical information, and through recordings and public concerts.

Comments

Post a Comment