Spasim

Spasim

| Spasim | |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Jim Bowery |

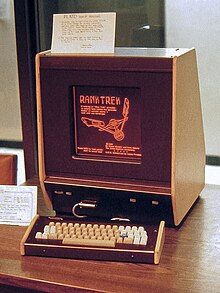

| Platform(s) | Mainframe computer (PLATO) |

| Release | March 1974 |

| Genre(s) | Space flight simulation |

| Mode(s) | Multiplayer |

Spasim is a 32-player 3D networked space flight simulation game and first-person space shooter[1] developed by Jim Bowery for the PLATO computer network and released in March 1974. The game features four teams of eight players, each controlling a planetary system, where each player controls a spaceship in 3D space in first-person view. Two versions of the game were released: in the first, gameplay is limited to flight and space combat, and in the second systems of resource management and strategy were added as players cooperate or compete to reach a distant planet with extensive resources while managing their own systems to prevent destructive revolts. Although Maze is believed to be the earliest 3D game and first-person shooter as it was largely complete by fall 1973, Spasim has been considered along with it to be one of the "joint ancestors" of the first-person shooter genre, due to uncertainty over Maze' development timeline.

The game was developed in 1974 at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign; Bowery was assisted in the second version by fellow student Frank Canzolino. Bowery encountered the PLATO system of thousands of graphics terminals remotely connected to a set of mainframe computers that January while assisting a computer art class. He was inspired to create the original game by the multiplayer PLATO action game Empire, and the second version by the concept of positive sum games. Spasim was one of the first 3D first-person video games; at one point, Bowery offered a reward to any person who could offer proof that Spasim was not the first. He also claims that Spasim was the direct initial inspiration for several other PLATO games, including Airace (1974) and Panther (1975).

Gameplay[edit]

Spasim is a multiplayer space flight simulation game, in which up to 32 players fly spaceships around 4 planetary systems. Players are grouped into teams of up to 8 players, with 1 team per system; players add their names to the rosters of the four teams, named Aggstroms, Diffractions, Fouriers, and Lasers, each with a different type of spaceship from Star Trek.[2][3] Players control their ships in first person in a 3D environment, with other ships appearing as wireframe models. There is no hidden line removal implemented on the models, meaning that the models appear see-through and the player can see the wireframe of the "back" of an object as well.[2] The positions of the planets and other players relative to the player update once a second.[4] Players can fire "phasers and torpedoes" to destroy other players' ships. Spasim was intended to include an educational component; players enter instructions to move their spaceships using polar coordinates, e.g. altitude and azimuth, along with acceleration, while their position in space is given in Cartesian coordinates.[5] Players can switch their perspective between their ship, their starting space station, and torpedoes they have launched, in addition to changing the angle and magnification zoom of their camera.[3] All controls are entered via single-key text inputs.[5]

The gameplay of the original version of Spasim is focused on space flight and combat.[5] An updated version of the game was released a few months after the initial release that added strategy and resource management; each team's planet has resources, population levels, and standard of living. Players spend their planet's supply of "anti-entropy" on powering their spaceship or managing their planet. Teams compete or cooperate in order to gain enough resources to reach a far distant planet. Mismanaging a team's resources or over-reliance on combat causes dissatisfaction on the players' planets, and can lead to a "planetary proletariat revolt" which greatly reduces the planet's population and resources.[5][3]

Development[edit]

The game was developed by Jim Bowery in early 1974 for the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign's PLATO computer network, which by the 1970s supported several thousand graphical terminals distributed worldwide, running processes on nearly a dozen different networked mainframe computers.[2] Bowery started working on the game, titled "spasim" as a contraction of "space simulation", as a student in January 1974 while assisting professor Leif Brush with the first computer art class at the university. Brush showed Bowery and the class a PLATO graphics terminal in the Lindquist Center on campus, and Bowery, intrigued, signed up for an individual studies course to assist professor Bobby Brown, who ran the lab with this terminal. Bowery learned to program on the computer, helped by other users such as John Daleske, the developer of Empire (1973), and Charles Miller, who later made Moria (1975). Bowery was inspired by the multiplayer and graphical nature of Empire, a space action game, to create something in the same vein.[5] Taking code for displaying a 3D vector graphics perspective previously written by Don Lee and Ron Resch, he designed 3D versions of the ships from Empire, and began adding more features to the game, including weapons inspired by Star Trek.[4][5]

The first version of Spasim, subtitled "An Investigation of Holographic Space", was launched in March 1974. A few months later, Bowery set out to rewrite the game, with the assistance of metallurgy student Frank Canzolino. At first, the pair optimized the 3D graphics of the game, but Bowery, inspired by the concept of positive sum games, or cooperative games, decided to delete the entire game code from the mainframe and start over, building in strategy and resource management elements into the base game instead of adding them on top.[5][6] Bowery designed the new version to penalize over-reliance on combat and incentivize cooperation as part of a philosophical stance on what he believed actual space expansion would require.[5] The second version of Spasim was developed over the course of three days, and the pair released it in July 1974.[5][6] Bowery released occasional updates to the game until he graduated; afterwards it was maintained by Steve Lionel, who added a tutorial on navigating in polar coordinates.[3]

Legacy[edit]

Bowery claims that Spasim had "quite a following" on the PLATO network and that there was "a late night cult" that was devoted to the game, though the emphasis in the second version of strategy over combat cut the playerbase in half.[5] Spasim is one of the first 3D first-person games ever made; at one point Bowery had a standing offer of $500 to any person who could find proof of an earlier such game, or $200 for an earlier game that mathematically modeled population versus resource availability and included space resources.[5] The very first is believed to be Maze, a maze game which ran on two connected computers at NASA in 1973 and was expanded to a full multiplayer game in fall 1973.[2][7] Spasim is considered, along with Maze, to be one of the "joint ancestors" of the first-person shooter genre, due to uncertainty over Maze' development timeline.[1][4][8]

According to Bowery, the initial release of Spasim inspired Silas Warner, one of the developers of Empire, to use Bowery's code in turn to develop the flight simulator game Airace for the PLATO system in 1975, which then lead to first Airfight, another flight simulator, and then the tank driving game Panther later that year.[2][6] Spasim has also been cited as a "spiritual ancenstor" of Elite (1984) and the line of Space trading games that came from it.[9]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Moss, Richard (2016-02-14). "Headshot: A visual history of first-person shooters". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2017-10-15. Retrieved 2017-10-14.

Jim Bowery's 32-player, 3D networked, first-person perspective space shooter Spasim—a kind of forebear to space combat sims Star Wars: X-Wing and Elite—got its first release on the PLATO computer around this time as well, effectively making Maze and Spasim joint ancestors of the FPS genre.

- ^ a b c d e Shahrani, Sam (2006-04-05). "A History and Analysis of Level Design in 3D Computer Games". Gamasutra. UBM. Archived from the original on 2012-12-02. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ a b c d Bowery, Jim (2013-01-06). Spasim (Video). YouTube. Archived from the original on 2017-02-16. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- ^ a b c Wolf, Mark J. P. (2012-11-02). "BattleZone and the Origins of First-Person Shooting Games". In Voorhees, Gerald A.; Call, Joshua; Whitlock, Katie (eds.). Guns, Grenades, and Grunts: First-Person Shooter Games. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-9144-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bowery, Jim (2001-04-10). "Spasim (1974) The First First-Person-Shooter 3D Multiplayer Networked Game". Jim Bowery. Archived from the original on 2001-04-10. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ^ a b c Williams, Andrew (2017-03-16). "Early 3D and Networked Games". History of Digital Games: Developments in Art, Design and Interaction. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-317-50381-1.

- ^ Moss, Richard (2015-05-21). "The first first-person shooter". Polygon. Archived from the original on 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

This is the story of Maze, the video game that lays claim to perhaps more "firsts" than any other — the first first-person shooter, the first multiplayer networked game, the first game with both overhead and first-person view modes, the first game with modding tools and more.

CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link) - ^ Davison, Pete (2013-07-17). "Blast from the Past: The Dawn of the First-Person Shooter". USGamer. Archived from the original on 2017-10-15. Retrieved 2017-10-14.

There's some debate over exactly what the first ever first-person perspective video game was, but it's either Maze War, an early example of a maze-based "deathmatch," and a game which pioneered the "flick-screen" grid-based movement that would be seen in classic dungeon crawlers such as Wizardry and Eye of the Beholder for many years afterwards; or Spasim, a space combat game which purports to be the first ever 3D multiplayer title.

- ^ Pinchbeck, Dan (2013-06-18). Doom: Scarydarkfast. University of Michigan Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-472-05191-5.

Comments

Post a Comment