Russell, New Zealand

Russell, New Zealand

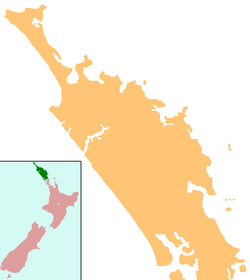

Russell | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 35°15′42″S 174°7′20″E / 35.26167°S 174.12222°E | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Region | Northland Region |

| District | Far North District |

| Settled | Early 19th century |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 762 |

| Postcode | 0202 |

Russell, known as Kororareka[a] in the early 19th century, was the first permanent European settlement and seaport in New Zealand. It is situated in the Bay of Islands, in the far north of the North Island.

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 786 | — |

| 2013 | 702 | −1.60% |

| 2018 | 762 | +1.65% |

| Source: [1] | ||

Russell had a population of 762 at the 2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 60 people (8.5%) since the 2013 census, and a decrease of 24 people (-3.1%) since the 2006 census. There were 339 households. There were 372 males and 390 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.95 males per female. Of the total population, 69 people (9.1%) were aged up to 15 years, 66 (8.7%) were 15 to 29, 351 (46.1%) were 30 to 64, and 276 (36.2%) were 65 or older. Figures may not add up to the total due to rounding.

Ethnicities were 86.6% European/Pākehā, 20.1% Māori, 1.2% Pacific peoples, 2.0% Asian, and 1.6% other ethnicities. People may identify with more than one ethnicity.

The percentage of people born overseas was 33.9, compared with 27.1% nationally.

Although some people objected to giving their religion, 54.3% had no religion, 31.5% were Christian, and 3.5% had other religions.

Of those at least 15 years old, 153 (22.1%) people had a bachelor or higher degree, and 102 (14.7%) people had no formal qualifications. The median income was $27,100. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 261 (37.7%) people were employed full-time, 114 (16.5%) were part-time, and 24 (3.5%) were unemployed.[1]

Much of the accommodation in the area consists of holiday homes or tourist accommodation.

History and culture[edit]

Māori settlement[edit]

Before the arrival of the Europeans, Russell was inhabited by Māori because of its salubrious climate and the abundance of food, fish and fertile soil. Russell was then known as Kororareka, and was a small settlement on the coast. The early European explorers like Britain's James Cook (1769) and France's Marion du Fresne (1772) have remarked that the area was quite prosperous.[2]

European settlement[edit]

When European and American ships began visiting New Zealand in the early 1800s, the indigenous Māori quickly recognised there were great advantages in trading with these strangers, whom they called tauiwi.[3] The Bay of Islands offered a safe anchorage and had a large Māori population. To attract ships, Māori began to supply food and timber. What the Māori population wanted was respect, plus firearms, alcohol, and other goods of European manufacture.

Kororareka developed as a result of this trade but soon earned a very bad reputation as a community without laws and full of prostitution. It became known as the "Hell Hole of the Pacific",[4] despite the translation of its name being "How sweet is the penguin" (kororā meaning blue penguin and reka meaning sweet).[5] European law had no influence and Māori law was seldom enforced within the town's area. Fighting on the beach at Kororareka in March 1830, between northern and southern hapū within the Ngāpuhi iwi, became known as the Girls' War.

On 30 January 1840 at the Christ Church, Governor Hobson read his Proclamations (which were the beginnings of the Treaty of Waitangi) in the presence of a number of settlers and the Maori chief Moka Te Kainga-mataa. A document confirming what had happened was signed at this time by around forty witnesses, including Moka, the only Maori signatory. The following week, the Treaty proceedings would then move across to the western side of the bay to Waitangi.[6]

By this time, Kororareka was an important mercantile centre and served as a vital resupply port for whaling and sealing operations. When the Colony of New Zealand was founded in that year, Hobson was reluctant to choose Kororareka as his capital, due to its bad reputation. Instead he purchased land at Okiato, situated five kilometres to the south, and renamed it Russell in honour of the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord John Russell. Captain Hobson soon decided that the move to the Okiato site was a mistake, and Auckland was selected as the new capital not long after.[7]

Kororareka was part of the Port of Russell, and after Russell (Okiato) became virtually deserted, Kororareka gradually came to be known as Russell as well. In January 1844, Governor Robert FitzRoy officially designated Kororareka as part of the township of Russell. Today, the name Russell applies only to Kororareka, while the former capital is known either by its original name of Okiato or as Old Russell.

Catholic mission[edit]

In 1841–42, Jean Baptiste Pompallier established a Roman Catholic mission in Russell, which contained a printing press for the production of Māori-language religious texts. His building, known as Pompallier Mission, remains in the care of Heritage New Zealand.

On 18 November 1844, while at anchor in the Bay of Islands, Mary Davis Wallis describes Kororarika [sic] as a town "which appears small, consisting of a few houses along the shore, and cottages scattered here and there on the slope of the hills behind. Nothing is to be seen back of the town but lofty hills not particularly verdant."[8]

Flagstaff dispute[edit]

At the beginning of the Flagstaff War in 1845 (touched off by the repeated felling and re-erection of the symbol of British sovereignty on Flagstaff Hill above the town), the town of Kororareka/Russell was sacked by Hōne Heke, after diversionary raids drew away the British defenders. The flagstaff was felled for the fourth time at the commencement of the Battle of Kororareka, and the inhabitants fled aboard British ships, which then shelled and destroyed most of the houses.[9]

Hōne Heke directed his warriors not to interfere with Christ Church and the Pompallier Mission.[citation needed]

Marae[edit]

The local Kororareka Marae is a traditional meeting ground of the Ngāpuhi hapū of Te Kapotai.[10][11]

Economy[edit]

Russell is now mostly a "bastion of cafés, gift shops and B&Bs".[9] Pompallier Mission, the historic printery/tannery/storehouse of the early Roman Catholic missionaries, Is the oldest surviving industrial building in New Zealand, while the town's Christ Church is the country's oldest surviving Anglican church.[12] The surrounding area also contains many expensive holiday homes, as well as New Zealand's most expensive rental accommodation, the Eagles Nest.[9] The photographer Laurence Aberhart lives here.

A car ferry across the Bay of Islands runs between Okiato and Opua, and is the main tourist access to Russell. There is a land connection, but this requires a substantial detour (the ferry route is only 2.3 kilometres, while the land route is 43.5 km[13]).

Education[edit]

Russell School is a coeducational full primary (years 1–8) school with a decile rating of 6 and a roll of 115.[14] The school opened in 1892.[15]

Notes[edit]

- ^ In modern orthography of the Māori language, this would be spelled Kororāreka.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Russell (103800). 2018 Census place summary: Russell

- ^ "PRE-CONTACT – TŌ MUA I A TAUIWI". Russell.

- ^ Binney, Judith (2007). Te Kerikeri 1770–1850, The Meeting Pool, Bridget Williams Books (Wellington) in association with Craig Potton Publishing (Nelson). ISBN 1877242381.

- ^ "Bay of Islands History". Jasons Travel Media.

- ^ McCloy, Nicola (2006). Whykickamoocow – curious New Zealand place names., Random House New Zealand.

- ^ King, M. (1949). Port in the North: A Short History of Russell. p. 37

- ^ NZETC. The Cyclopedia of New Zealand. The Seat Of Government, Page 8. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ Wallis, Mary (a lady) (2002). Life in Feejee : five years among the cannibals, a woman's account of voyaging the Fiji Islands aboard the "Zotoff" (1844–49). Santa Barbara, Calif.: Narrative Press. p. 10. ISBN 1-58976-208-8.

- ^ a b c Russell (from the Lonely Planet New Zealand, 13th Edition, September 2006.

- ^ "Te Kāhui Māngai directory". tkm.govt.nz. Te Puni Kōkiri.

- ^ "Māori Maps". maorimaps.com. Te Potiki National Trust.

- ^ Petriello, Amy (28 August 2005). "Russell – the sleeping beauty". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Google Maps Directions

- ^ "Te Kete Ipurangi – Russell School, Bay of Islands|Russell School". Ministry of Education. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012.

- ^ "Cosmopolitan Russell". Russell Lights. 9 (3). February 2006.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Russell. |

- Russell (a local page about the town)

- Russell Info (tourism information from bayofislands.net)

Comments

Post a Comment