Elaine massacre

Elaine massacre

| Part of Mass racial violence in the United States, Nadir of American race relations and Red Summer | |

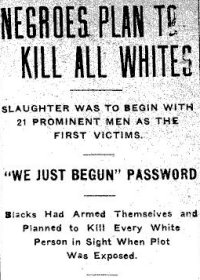

Inflammatory headline in the Arkansas Gazette, October 3, 1919 | |

| Date | September 30, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Hoop Spur, Phillips County, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Also known as | Elaine Massacre |

| Participants | residents of Phillips County, Arkansas |

| Deaths | 100–237 black people,[1] 5 whites[2][3] |

The Elaine massacre or the Elaine race riot occurred on September 30–October 1, 1919, at Hoop Spur in the vicinity of Elaine in rural Phillips County, Arkansas. Although official records of the time state that eleven black men and five white men were killed,[4] estimates of the actual number of black people who were killed range from 100 to 237. According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, "the Elaine Massacre was by far the deadliest racial confrontation in Arkansas history and possibly the bloodiest racial conflict in the history of the United States".[5][6]

Because of the widespread attacks which white mobs committed against blacks during this period of racial terrorism against black citizens, the Equal Justice Initiative of Montgomery, Alabama classified the black deaths as lynchings in its 2015 report on the lynching of African Americans in the South.[7]

Background[edit]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Arkansas |

|

| |

Located in the Arkansas Delta, Phillips County had historically been developed for cotton plantations, and its land was worked by African-American slaves before the Civil War. In the early 20th century the county's population was still predominantly black, because most freedmen and their descendants had stayed on the land as illiterate farm workers and sharecroppers.

African Americans outnumbered whites in the area around Elaine by a ten-to-one ratio, and by three-to-one in the county overall.[5] White landowners controlled the economy, selling cotton on their own schedule, running high-priced plantation stores where farmers had to buy seed and supplies, and settling accounts with sharecroppers in lump sums, without listing items.[5]

The Democratic-dominated legislature had disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites in the 1890s by creating barriers to voter registration. It excluded them from the political system via the more complicated Election Law of 1891 and a poll tax amendment passed in 1892. The white-dominated legislature enacted Jim Crow laws that established racial segregation and institutionalized Democratic efforts to impose white supremacy. The decades around the turn of the century were the period of the highest rate of lynchings across the South.

Sharecropping, the African Americans had been having trouble in getting settlements for the cotton they raised on land owned by whites. Both the Negroes and the white owners were to share the profits when the crop was sold for the year. Between the time of planting and selling, the sharecroppers took up food, clothing, and necessities at excessive prices from the plantation store owned by the planter.

— O.A. Rogers, Jr., President of the Arkansas Baptist College in Little Rock, Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Summer 1960 issue[4]

The landowner sold the crop whenever and however he saw fit. At the time of settlement, landowners generally never gave an itemized statement to the black sharecroppers of accounts owed, nor details of the money received for cotton and seed. The farmers were disadvantaged as many were illiterate. It was an unwritten law of the cotton country that the sharecroppers could not quit and leave a plantation until their debts were paid. The period of the year around accounts settlement was frequently the time of most lynchings of blacks throughout the South, especially if times were poor economically. As an example, many Negroes in Phillips County, whose cotton was sold in October 1918, did not get a settlement before July of the following year. They often amassed considerable debt at the plantation store before that time, as they had to buy supplies, including seed, to start the next season.

Black farmers began to organize in 1919 to try to negotiate better conditions, including fair accounting and timely payment of monies due them by white landowners. Robert L. Hill, a black farmer from Winchester, Arkansas, had founded the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. He worked with farmers throughout Phillips County. Its purpose was "to obtain better payments for their cotton crops from the white plantation owners who dominated the area during the Jim Crow era. Black sharecroppers were often exploited in their efforts to collect payment for their cotton crops."[5]

Whites tried to disrupt such organizing and threatened farmers.[8] The union had hired a white law firm in the capital of Little Rock to represent the black farmers in getting fair settlements for their 1919 cotton crops before they were taken away for sale. The firm was headed by Ulysses S. Bratton, a native of Searcy County and former assistant federal district attorney.[8]

The postwar summer of 1919 had already been marked by deadly race riots against black Americans in more than three dozen cities across the country, including Chicago, Knoxville, Washington, DC, and Omaha, Nebraska. Competition for jobs and housing in crowded markets following World War I as veterans returned to society resulted in outbreaks of racial violence, usually of ethnic whites against blacks. Having served their country in the Great War, African-American veterans resisted racial discrimination and violence. In 1919 blacks vigorously fought back when their communities were attacked. Labor unrest and strikes took place in several cities as workers tried to organize. As industries hired blacks as strikebreakers in some cities, worker resentment against them increased.[5]

Events[edit]

The Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America had organized chapters in the Elaine area in 1918-19.[9] On September 29, representatives met with about 100 black farmers at a church near Elaine to discuss how to obtain fairer settlements from landowners. Whites had resisted union organizing by the farmers and often spied on or disrupted such meetings. Approximately 100 African-American farmers, led by Robert L. Hill, the founder of the union, met at a church in Hoop Spur, near Elaine in Phillips County. Union advocates brought armed guards to protect the meeting. When two deputized white men and a black trustee arrived at the church, shots were exchanged. Railroad Policeman W.D. Adkins, employed by the Missouri Pacific Railroad was killed[10][11] and the other white man wounded; it was never determined who shot first.

According to Revolution in the Land: Southern Agriculture in the 20th Century (2002), in a section called "The Changing Face of Sharecropping and Tenancy":[12]

The black trustee raced back to Helena, the county seat of Phillips County, and alerted officials. A posse was dispatched and within a few hours hundreds of white men, many of them the "low down" variety, began to comb the area for blacks they believed were launching an insurrection. In the end, over a hundred African Americans and five white men were killed. Some estimates of the black death toll range in the hundreds. Allegations surfaced that the white posse and even U.S. soldiers who were brought in to put down the so called "rebellion" had massacred defenseless black men, women and children.

The parish sheriff called for a posse to capture suspects in the killing. The county sheriff organized the posse and whites gathered to put down what was rumored as a "black insurrection".[5] Violence expanded beyond the church. Additional armed white men entered the county from outside to support the hunt and a mob formed of 500 to 1,000 armed men. They attacked blacks on sight across the county. Local whites requested help from Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough, citing a "Negro uprising". Sensational newspaper headlines published by the Little Rock Gazette and others reported that an "insurrection" was occurring, and that blacks had planned to murder white leaders.[13][14]

Governor Brough contacted the War Department and requested Federal troops. After considerable delay, nearly 600 U.S. troops arrived, finding the area in chaos.[15] White men roamed the area randomly attacking and killing blacks.[5] Fighting in the area lasted for three days before the troops ended the violence. The federal troops disarmed both parties and arrested 285 black residents, putting them in stockades for investigation until being vouched for by their employers and protection.[5]

Although official records of the time count eleven black men and five white men killed,[4][16] there are estimates from 100 to 237 African Americans killed, and more wounded. At least two and possibly more victims were killed by Federal troops. The exact number of blacks killed is unknown because of the wide rural area in which they were attacked.[2][3][6][5]

Press coverage[edit]

A dispatch from Helena, Arkansas to the New York Times, datelined October 1, said: "Returning members of the [white] posse brought numerous stories and rumors, through all of which ran the belief that the rioting was due to propaganda distributed among the negroes by white men."[17]

The next day's report added detail:

Additional evidence has been obtained of the activities of propagandists among the negroes, and it is thought that a plot existed for a general uprising against the whites." A white man had been arrested and was "alleged to have been preaching social equality among the negroes." Part of the headline was: "Trouble Traced to Socialist Agitators."[18]

A few days later a Western Newspaper Union dispatch was captioned, "Captive Negro Insurrectionists."[19]

Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough appointed a Committee of Seven to investigate. The group was composed of prominent local white businessmen. Without talking to any of the black farmers, they concluded that the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America was a Socialist enterprise and "established for the purpose of banding negroes together for the killing of white people."[20] This version by the white power structure has persisted in many histories of the riot.[citation needed]

NAACP involvement[edit]

The NAACP promptly released a statement from a contact in Arkansas providing another account of the origins of the violence:

The whole trouble, as I understand it, started because a Mr. Bratton, a white lawyer from Little Rock, Ark., was employed by sixty or seventy colored families to go to Elaine to represent them in a dispute with the white planters relative to the sale price of cotton.

It referred to a report in the Commercial Appeal of Memphis, Tennessee on October 3 that quoted Bratton's father:[21]

It had been impossible for the negroes to obtain itemized statements of accounts, or in fact to obtain statements at all, and that the manager was preparing to ship their cotton, they being sharecroppers and having a half interest therein, off without settling with them or allowing them to sell their half of the crop and pay up their accounts.... If it's a crime to represent people in an effort to make honest settlements, then he has committed a crime.

The NAACP sent its Field Secretary, Walter F. White, from New York City to Elaine in October 1919 to investigate events. White was of mixed, majority-European ancestry; blond and blue-eyed, he could pass for white. He was granted credentials from the Chicago Daily News. He gained an interview with Governor Charles Hillman Brough, who gave him a letter of recommendation for other meetings with whites, as well as an autographed photograph.

White had been in Phillips County for a brief time when he learned there were rumors floating about him. He quickly took the first train back to Little Rock. The conductor told the young man that he was leaving "just when the fun is going to start," because they had found out that there was a "damned yellow nigger passing for white and the boys are going to get him." When White asked what the boys would do to the man, the conductor told White that "when they get through with him he won't pass for white no more!"[22]

White had time to talk with both black and white residents in Elaine. He reported that local people said that up to 100 blacks had been killed. White published his findings in the Daily News, the Chicago Defender, and The Nation, as well as the NAACP's magazine The Crisis.[2] He "characterized the violence as an extreme response by white landowners to black unionization."[23]

Governor Brough asked the United States Post Office Department to prohibit the mailing of the Chicago Defender and Crisis to Arkansas, while local officials attempted to enjoin distribution of the Defender. Years later, White said in his memoir that people in Elaine told him that up to 200 blacks had been killed.[3]

Trials[edit]

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (February 2017) |

In October and November 1919, an all-white Arkansas state grand jury returned indictments against 122 blacks. Since most blacks had been disenfranchised by Arkansas' 1891 Election Law and 1892 poll tax amendment, which created barriers to voter registration, blacks as non-voters were excluded from juries. All-white juries rendered verdicts on the defendants in trials following the Elaine race riot. The only men prosecuted for these events were 122 African Americans, with 73 charged with murder.

Those blacks willing to testify against others and to work without shares for terms as determined by their landlords, were set free. Those who refused to comply with those conditions, or were labeled as ringleaders or were judged unreliable, were indicted. According to the affidavits later supplied by the defendants, many of the prisoners had been beaten, whipped or tortured by electric shocks to extract testimony or confessions. They were threatened with death if they recanted their testimony. A total of 73 suspects were charged with murder; other charges included conspiracy and insurrection.[2]

The trials were held in 1920 in the county courthouse in Elaine, Phillips County. Mobs of armed whites milled around the courthouse. Some of the white audience in the courtroom also carried arms. The lawyers for the defense did not subpoena witnesses for the defense and did not allow their clients to testify.[5]

Twelve of the defendants (who became known as the 'Arkansas Twelve' or 'Elaine Twelve') were convicted of murder and sentenced to death in the electric chair[6] by all-white juries for murder of the white deputy at the church, most of them as "accomplices" in the murder of Adkins at the church. Others were convicted of lesser charges and sentenced to prison. The defense lawyer of one defendant did not interview any witnesses, ask for a change of venue, nor challenge any jurors.[5] The trials of these twelve lasted less than an hour in many cases; the juries took fewer than ten minutes to deliberate before pronouncing each man guilty and sentencing them to death. The Arkansas Gazette applauded the trials as the triumph of the "rule of law," because none of the defendants were lynched. These men became known as the "Elaine Twelve."[5]

After those convictions, 36 of the remaining defendants chose to plead guilty to second-degree murder rather than face trial. Sixty-seven other defendants were convicted of various charges and sentenced to terms up to 21 years.[5] When the cases were remanded to the state court, the six 'Moore' defendants settled with the lower court on lesser charges and were sentenced to time already served.

Appeals[edit]

During appeals, the death penalty cases were separated. The NAACP took on the task of organizing the defendants' appeals. The NAACP assisted the defendants in the appeals process, raising money to hire a defense team, which it helped direct. For a time, the NAACP tried to conceal its role in the appeals, given the hostile reception to its reports on the rioting and the trials. Once it undertook to organize the defense, it went to work vigorously, raising more than $50,000 and hiring Scipio Africanus Jones, a highly respected African-American attorney from Arkansas, and Colonel George W. Murphy, a 79-year-old Confederate veteran and former Attorney General for the State of Arkansas.[5] Moorfield Storey, descended from Boston abolitionists and founding president of the NAACP since 1909, became part of the team when the Moore cases went to the Supreme Court. He had been president of the American Bar Association in 1895.[8]

The defendants' lawyers obtained reversal of the verdicts by the Arkansas Supreme Court in six of the twelve death penalty cases, known as the Ware defendants.[5] The grounds were that the jury had failed to specify whether the defendants were guilty of murder in the first or second degree; those cases (known as Ware et al.) were sent back to the lower court for retrial.[5] The lower court retried the defendants beginning on May 3, 1920. On the third day of the trials, Murphy collapsed in the courtroom.[24]

Scipio Jones had to carry most of the responsibility for the remaining trials. The all-white juries quickly convicted the six defendants of second-degree murder and sentenced them to 12 years each in prison. Jones appealed these convictions, which were overturned by the State Supreme Court. It found that the exclusion of blacks from the juries resulted in a lack of due process for the defendants, based on violations of the Fourteenth Amendment (especially Due Process Clause) and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, due to exclusion of blacks from the juries.[8] The lower courts failed to retry the men within the two years required by Arkansas law, and the defense finally gained their release in 1923.[8]

Moore et al.[edit]

The Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the death sentences of Moore and the other five defendants. It rejected the challenge to the all-white juries as untimely, and found that the mob atmosphere and use of coerced testimony did not deny the defendants the due process of law. Those defendants unsuccessfully petitioned the United States Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari from the Arkansas Supreme Court's decision.[25]

The defendants next petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus, alleging that the proceedings that took place in the Arkansas state court, while ostensibly complying with trial requirements, in fact complied only in form. They argued that the accused had not been adequately defended and were convicted under the pressure of the mob, with blatant disregard for their constitutional rights.[25]

The defendants originally intended to file their petition in Federal district court, but the only sitting judge was assigned to other judicial duties in Minnesota at the time and would not return to Arkansas until after the defendants' scheduled execution date. Judge John Ellis Martineau of the Pulaski County chancery court issued the writ. Although the writ was later overturned by the Arkansas Supreme Court, his action postponed the execution date long enough to permit the defendants to seek habeas corpus relief in Federal court.[25]

U.S. District Judge Jacob Trieber issued another writ. The State of Arkansas defended the convictions from a narrowly legalistic position, based on the US Supreme Court's earlier decision in Frank v. Mangum (1915). It did not dispute the defendants' evidence of torture used to obtain confessions nor of mob intimidation at the trial, but the state argued that, even if true, these elements did not amount to a denial of due process. The United States district court agreed, denying the writ, but it found there was probable cause for an appeal and allowed the defendants to take their case to the U.S. Supreme Court.[25]

In Moore v. Dempsey 261 U.S. 86 (1923),[25] the United States Supreme Court vacated these six convictions on the grounds that the mob-dominated atmosphere of the trial and the use of testimony coerced by torture denied the defendants' due process as required by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[8] Prominent Little Rock attorney George Rose wrote a letter to outgoing Governor Thomas McRae requesting that he find a way to release the remaining defendants if they agreed to plead guilty to second-degree murder. Rose's letter was an attempt to prevent Governor-Elect Thomas Jefferson Terral, a known member of the Ku Klux Klan, from getting involved in the matter.[26][27]

Just hours before Governor McRae left office in 1925, he contacted Scipio Jones to inform him that indefinite furloughs had been issued for the remaining defendants.[5] He freed these six men in 1925 in the closing days of his administration. Jones used the furloughs to obtain release of the prisoners under cover of darkness. He arranged for these men to be quickly escorted out of state to prevent them from being lynched. The NAACP helped them leave the state safely.[8]

Aftermath[edit]

The Supreme Court's decision marked the beginning of an era in which the Supreme Court gave closer scrutiny to criminal justice cases and reviewed state actions against the Due Process Clause and the Bill of Rights. A decade later, the Supreme Court reviewed the case of the Scottsboro boys. The victory for the Elaine defendants gave the NAACP greater credibility as the champion of African Americans' rights. Walter F. White's risk-taking investigation and report contributed to his advancing in the organization. He later was selected as executive secretary of the NAACP, essentially the chief operating officer, and served in this position for decades, leading the organization in additional legal challenges and civil rights activism.

"It is documented that five whites, including a soldier died at Elaine, but estimates of African American deaths, made by individuals writing about the Elaine affair between 1919-25, range from 20 to 856; if accurate, these numbers would make it by far the most deadly conflict in the history of the United States.[28] The Arkansas Encyclopedia of History and Culture notes that estimates of African-American deaths range into the "hundreds."[29]

Since the late 20th century, researchers have begun to investigate the Elaine race riot more thoroughly. For decades, the riot and numerous murders were too painful to be discussed openly in the region. The wide-scale violence ended union organizing among black farmers. White oppression continued, threatening every black family. Historian Robert Whitaker says, "As with many racial histories of this kind," it was "one of those shameful events best not talked about."[24][6]

Another reason for silence was that the second Ku Klux Klan began to be active in Arkansas in 1921, concentrating in black-majority areas. It used intimidation and attacks to keep blacks suppressed. Author Richard Wright grew up in Phillips County and discusses it in his autobiography Black Boy. He wrote that when he questioned his mother about why their people didn't fight back, "the fear that was in her made her slap me into silence."[24]

A 1961 article, "Underlying Causes of the Elaine Riot," claimed that blacks were planning an insurrection, based on interviews with whites who had been alive at the time, and that they were fairly treated by planters of the area. It repeated rumors of 1919 that certain planters were targeted for murder.[11] This view has been generally discounted by historians publishing since the late 20th century.

In early 2000, a conference on the Elaine riot was held at the Delta Cultural Center in the county seat of Helena, Arkansas.[5][30] It was an effort to review the facts but did not result in "closure" for the people of Phillips County.[5] The Associated Press spoke with author Grif Shockley, who has published a book on the riot. He said that in 2000, there were still two versions of the riot, which he characterized as the "white" version, related to their idea that the union planned an attack on whites, and a "black" version, related to farmers' efforts to gain fair settlements of their crops. Shockley said there "was plenty of evidence to say whites attacked blacks indiscriminately."[31] Local electoral offices were divided between the races in West Helena and the county.[31]

Memorial[edit]

In September, 2019, 100 years after the event, an Elaine Massacre Memorial was unveiled.[6] A Memorial Willow Tree planted at the memorial in April, 2019, was cut down in August, and a "memorial tag" stolen.[32]

Representation in other media[edit]

- Wormser, Richard, director. The Elaine Riot: Tragedy & Triumph. VHS Documentary. Little Rock: Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, 2002.

See also[edit]

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Nadir of American race relations

- Racism in the United States

- Red Summer (1919)

- Moore v. Dempsey (1923)

- Racial equality proposal, 1919

- List of ethnic riots

- List of events named massacres

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

References[edit]

- ^ Arkansas Assembly 2017

- ^ a b c d Elaine Massacre, Arkansas Encyclopedia of History and Culture; accessed April 3, 2008.

- ^ a b c Walter Francis White, A Man Called White: The Autobiography of Walter White, University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA reprint, 1995, pg. 49.

- ^ a b c Rogers, O. A. (1960). The Elaine Race Riots of 1919. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 19 (2): 142.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Elaine Massacre". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- ^ a b c d e Krug, Teresa (18 August 2019). "A rural town confronts its buried history of mass killings of black Americans". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Robertson, Campbell (February 10, 2015). "History of Lynchings in the South Documents Nearly 4,000 Names". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g Walter L. Brown, "Reviewed Work: A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases by Richard C. Cortner", The Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. 48, No. 3 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 289-91, via JSTOR; accessed February 13, 2017.

- ^ McCarty, J. (1978). The Red Scare in Arkansas: A Southern State and National Hysteria. The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 37(3), 264-277.

- ^ ODMP memorial W.D. Adkins

- ^ a b Butts, J. W., and Dorothy James. "The Underlying Causes of the Elaine Riot of 1919", Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Spring 1961): 95–104, via JSTOR

- ^ "Electronic History Resources, online since 1990". Historical Text Archive. 1956-11-04. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- ^ [Ida B. Wells Wells-Barnett, I. B.] (1920). [The Arkansas Race Riot https://archive.org/details/TheArkansasRaceRiot/].

- ^ (See scanned Gazette headlines on this page)

- ^ Desmarais, Ralph H. (1974). "Military Intelligence Reports on Arkansas Riots: 1919-1920". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 33 (2): 175. doi:10.2307/40038126.

- ^ Waterman, J. S., & Overton, E. E. (1932). The Aftermath of Moore v. Dempsey. . Louis L. Rev., 18, 117.

- ^ New York Times: "Nine Killed in Fight with Arkansas Posse", October 2, 1919; accessed January 27, 2010

- ^ "Six More are Killed in Arkansas Riots", New York Times, October 3, 1919; accessed January 27, 2010.

- ^ New York Times: "Captive Negro Insurrectionists", October 12, 1919; accessed January 27, 2010.

- ^ Eric M. Freedman, Habeas Corpus: Rethinking the Great Writ of Liberty (New York University Press, 2001), p. 68

- ^ New York Times: "Lays Riots to Cotton Row", October 13, 1919; accessed January 27, 2010.

- ^ "Walter White: Mr. NAACP, 2003, p. 52"

- ^ Jason McCollom, "Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA)", 2015, Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture; accessed February 18, 2016

- ^ a b c JAY JENNINGS, "12 Innocent Men", New York Times, June 22, 2008; accessed February 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86 (1923)

- ^ "Thomas J. Terral". oldstatehouse.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ Charles C. Alexander, "Defeat, Decline, Disintegration: the Ku Klux Klan in Arkansas, 1924 and After", Arkansas Historical Quarterly, XXII (Winter 1963), p. 317

- ^ Grif Stockley, Blood in their Eyes: The Elaine Race Massacres of 1919 (Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press, 2001), xiv.

- ^ "Elaine race riot", Encyclopedia of Arkansas; accessed February 13, 2017.

- ^ Reconsidering the Elaine Race Riots of 1919, Conference, February 10–11, 2000, Delta Cultural Center

- ^ a b Associated Press, "Conference to dredge up bloody past of 1919 Arkansas race riot", Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, February 2009

- ^ "Arkansas: tree honoring 1919 Elaine Massacre victims cut down". The Guardian. August 26, 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Bowden, Charles (November 2012). "Arkansas Delta, 40 Years Later". National Geographic. 222 (5): 128. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- Butts, J. W., and Dorothy James. "The Underlying Causes of the Elaine Riot of 1919", Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Spring 1961): 95–104, via JSTOR.

- Collins, Ann V. All Hell Broke Loose: American Race Riots from the Progressive Era through World War II. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2012.

- Cortner, Richard, A Mob Intent On Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases; Wesleyan University Press ISBN 0-8195-5161-9

- Dillard, Tom. "Scipio A. Jones." Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Autumn 1972): 201–219.

- Janken, Kenneth Robert. Walter White: Mr. NAACP. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina, 2006; ISBN 0-807-85780-7

- Krugler, David (February 16, 2015). "America's Forgotten Mass Lynching: When 237 People Were Murdered In Arkansas". Daily Beast.

- McCool, B. Boren. Union, Reaction, and Riot: The Biography of a Rural Race Riot. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1970.

- McWhirter, Cameron. Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. New York: St. Martin's, 2011.

- Smith, C. Calvin, ed. "The Elaine, Arkansas, Race Riots, 1919." Special Issue. Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 32 (August 2001).

- Stockley, Grif Jr. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Race Massacre of 1919, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 2001

- Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice That Remade a Nation. New York: Random House, Inc. 2008; ISBN 978-0-307-33982-9 (0-307-33982-3)

External links[edit]

- Facebook site of the Elaine Legacy Center

- Reconsidering the Elaine Race Riots of 1919, Material and website for Conference, February 10-11, 2000, Delta Cultural Center

- 1919 riots

- 1919 in Arkansas

- African-American history of Arkansas

- Mass murder in 1919

- Massacres in the United States

- October 1919 events

- Phillips County, Arkansas

- Protest-related deaths

- Racially motivated violence against African Americans

- Riots and civil disorder in Arkansas

- Red Summer

- September 1919 events

- White American riots in the United States

- Lynching deaths in Arkansas

Comments

Post a Comment