Protestant Union

Protestant Union

The Protestant Union (German: Protestantische Union), also known as the Evangelical Union, Union of Auhausen, German Union or the Protestant Action Party, was a coalition of Protestant German states. It was formed on May 14, 1608 by Frederick IV, Elector Palatine in order to defend the rights, land and safety of each member. It included both Calvinist and Lutheran states, and dissolved in 1621.

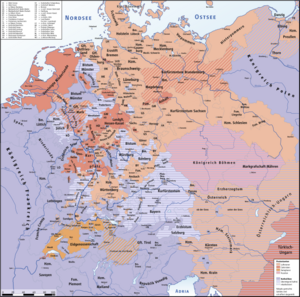

The union was formed following two events. Firstly, the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II and Bavarian Duke Maximilian I reestablished Catholicism in Donauwörth in 1607. Secondly, by 1608, a majority of the Imperial Diet had decided that the renewal of the 1555 Peace of Augsburg should be conditional upon the restoration of all church land appropriated since 1552. The Protestant princes met in Auhausen, and formed a coalition of Protestant states under the leadership of Frederick IV on May 14, 1608. In response, the Catholic League organized the following year, headed by Duke Maximilian.[1]

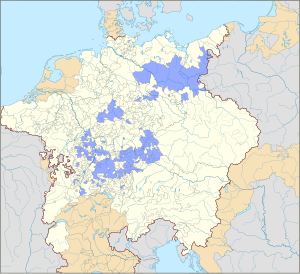

Members of the Protestant Union included the Palatinate, Neuburg, Württemberg, Baden-Durlach, Ansbach, Bayreuth, Anhalt, Zweibrücken, Oettingen, Hesse-Kassel, Brandenburg, and the free cities of Ulm, Strasbourg, Nuremberg, Rothenburg, Windsheim, Schweinfurt, Weissenburg, Nördlingen, Schwäbisch Hall, Heilbronn, Memmingen, Kempten, Landau, Worms, Speyer, Aalen and Giengen.[2]

However, the Protestant Union was weakened from the start by the non-participation of several powerful German Protestant rulers, notably the Elector of Saxony. The Union was also beset by internal strife between its Lutheran and Calvinist members.[3]

In 1619, Frederick V of the Palatinate accepted the crown of Bohemia in opposition to Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II. On July 3, 1620, the Protestant Union signed the Treaty of Ulm (German: Ulmer Vertrag), declaring neutrality and declining to support Frederick V.[4] In January 1621, Ferdinand II imposed an imperial ban upon Frederick V and moved his right to elect an emperor to Maximilian. Electoral Palatinate also lost the Upper Palatinate to Bavaria. The Protestant Union met in Heilbronn in February and formally protested Ferdinand's actions. He ignored this complaint and ordered the Protestant Union to disband its army. The members of the union complied with Ferdinand's demand under the Mainz accord in May, and on May 14, 1621, it was formally dissolved.[5]

A new separate union without connection to this one emerged twelve years later, the Heilbronn League. It allied some Protestant states in western, central and southern Germany, and fought against the Holy Roman Emperor under the guidance of Sweden and France, which were at the same time parties to that league.

Guidelines of the Protestant Union[edit]

Intending to strengthen the security provided by the Peace of Augsburg, Protestants formed the union in 1608. Its leaders created guidelines and agreements to live by as follows:

- Each member shall keep in good faith with the order and their heirs, land and people, and no one shall enter into any other alliance.

- Each member of the union should keep a secret correspondence effectively to inform each other of all dangerous and offensive affairs which may threaten each other's heirs, land and people, and to this purpose each will keep in good contact with one another.

- Whenever important matters arise that concern the well-being of the union, the members of the union will help each other with faithful advice in order to uphold each and every one as much as possible.

- The wish of the union in matters concerning the liberties and high jurisdictions of the German Electors and Estates should be presented and pressed at subsequent Imperial and Imperial Circle assemblies, and not merely left to secret correspondence with each other.

- The union shall not affect our disagreement on several points of religion, but that notwithstanding these, we have agreed to support each other. No member is to allow an attack on any other in books or through the pulpit, nor give cause for any breach of the peace, while at the same time leaving untouched the theologian's rights of disputation to affirm the word of God.

- If one of the members of the union is attacked, the remaining members of the union shall immediately come to his aid with all the resources of the union.[6]

Timeline[edit]

In 1555, the Peace of Augsburg was signed by Charles V and Lutheran princes. This treaty gave Roman Catholic and Lutheran princes the freedom to decide the religion which their respective state would be under, but gave no such protection to Calvinist princes. In 1608, Protestant princes formed the alliance known as Protestant Union. The next year, the Catholic League was created. In 1610, the Union intervened in the War of the Jülich Succession.[7] In 1618, the Thirty Years' War began with the outbreak of the Bohemian Revolt. Frederick V, Elector Palatine, accepted the crown of Bohemia the following year. The Union declared its neutrality in the conflict between Frederick and the Catholic League in the 1620 Treaty of Ulm. The Union dissolved the next year.

See also[edit]

- Other Protestant leagues:

- League of Torgau (1526-1531), the earliest league of Protestant princes against the Catholic League of Dessau, succeeded by the Schmalkaldic League

- Schmalkaldic League (1531-1546), a league of Protestant princes against the Holy Roman Emperor

- Heilbronn League (1633-1648), a league of western and southern Protestant German states under Swedish and French guidance

Notes[edit]

- ^ Anderson 1999, pp. 14–15; Wilson 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Ward 1905, p. 725; Schönstädt 1978, p. 305.

- ^ Anderson 1999, pp. 135, 215.

- ^ Wedgwood 1938, pp. 98–99, 110–11.

- ^ Wedgwood 1938, pp. 133–34.

- ^ Hofmann n.d.

- ^ Anderson 1999, p. 82.

References[edit]

- Anderson, Alison D. (1999). On the Verge of War: International Relations and the Jülich-Kleve Succession Crises (1609–1614). Boston: Humanities Press. ISBN 978-0-391-04092-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hofmann, H.H. (n.d.). "The Protestant Union, 1608". The Crown & The Cross. Retrieved 25 October 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schönstädt, Hans-Jürgen (1978). Antichrist, Weltheilsgeschehen und Gottes Werkzeug. Römische Kirche, Reformation, und Luther im Spiegel des Reformationsjubiläums 1617 (in German). Wiesbaden: Steiner. ISBN 9783515027472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ward, Adolphus William (1905). "The Empire Under Rudolf II". In Ward, Adolphus William; Prothero, George Walter; Leathes, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Modern History, Volume III: The Wars of Religion. New York and London: Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wedgwood, Cicely Veronica (1938). The Thirty Years War. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 9781590171462.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Peter H. (2010). The Thirty Years War: A Sourcebook. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-24205-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading[edit]

- Rickard, J. (17 November 2000), Thirty Years' War (1618–48), http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/wars_thirtyyears.html

- Helfferich, Tryntje. The Thirty Years' War: A Documentary History. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2009. Print.

- Bohemian Protestants and the Calvinist Churches.

- Odložilík, Otakar. Church History, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Dec., 1939), pp. 342–355. Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society of Church History. Article Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3160169

Comments

Post a Comment