Georges Brassens

Georges Brassens

Georges Brassens | |

|---|---|

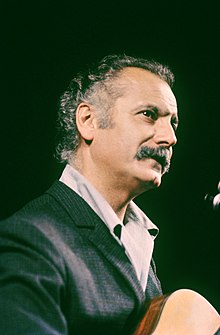

Georges Brassens in concert at the Théâtre national populaire, September–October 1966. | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Georges Charles Brassens |

| Born | 22 October 1921 Cette (now Sète), France |

| Died | 29 October 1981 (aged 60) Saint-Gély-du-Fesc, France |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) | Singer-songwriter |

| Instrument(s) | Acoustic guitar, Piano, Organ, Banjo, Drums |

| Years active | 1951–1981 |

| Labels | Universal Music |

Georges Charles Brassens (French pronunciation: [ʒɔʁʒ(ə) ʃaʁl bʁasɛ̃s]; 22 October 1921 – 29 October 1981) was a French singer-songwriter and poet.

As an iconic figure in France, he achieved fame through his elegant songs with their harmonically complex music for voice and guitar and articulate, diverse lyrics. He is considered one of France's most accomplished postwar poets. He has also set to music poems by both well-known and relatively obscure poets, including Louis Aragon (Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux), Victor Hugo (La Légende de la Nonne, Gastibelza), Paul Verlaine, Jean Richepin, François Villon (La Ballade des Dames du Temps Jadis), and Antoine Pol (Les Passantes).

During World War II, he was forced by the Germans to work in a labor camp at a BMW aircraft engine plant in Basdorf near Berlin in Germany (March 1943). Here Brassens met some of his future friends, such as Pierre Onténiente, whom he called Gibraltar because he was "steady as a rock." They would later become close friends.

After being given ten days' sick leave in France, he decided not to return to the labor camp. Brassens took refuge in a small cul-de-sac called "Impasse Florimont," in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, a popular district, where he lived for several years with its owner, Jeanne Planche, a friend of his aunt. Planche lived with her husband Marcel in relative poverty: without gas, running water, or electricity. Brassens remained hidden there until the end of the war five months later, but ended up staying for 22 years. Planche was the inspiration for Brassens's song Jeanne.

He wrote and sang, with his guitar, more than a hundred of his poems. Between 1952 and 1976, he recorded fourteen albums that include several popular French songs such as Les copains d'abord, Chanson pour l'Auvergnat, La mauvaise réputation, and Mourir pour des idées. Most of his texts are tinged with black humour and are often anarchist-minded.

In 1967, he received the Grand Prix de Poésie of the Académie française.

Apart from Paris and Sète, he lived in Crespières (near Paris) and in Lézardrieux (Brittany).

Biography[edit]

Childhood and education[edit]

Brassens was born in Sète, a commune in the Hérault department of the Occitanie region, to a French father and an Italian mother from the town of Marsico Nuovo (in the province of Potenza, Basilicata).[1]

Brassens grew up in the family home in Sète with his mother, Elvira Dagrosa, father, Jean-Louis, half-sister, Simone (daughter of Elvira and her first husband, who was killed in World War I), and paternal grandfather, Jules. His mother, whom Brassens labeled a "missionary for songs" (militante de la chanson), came from southern Italy (Marsico Nuovo in Basilicata),[2] was a devout Roman Catholic, while his father was an easy-going, generous, openminded, anticlerical man. Brassens grew up between these two starkly contrasting personalities, who nonetheless shared a love for music. His mother, Simone, and Jules, were always singing. This environment imparted to Brassens a passion for singing that would come to define his life. At the time he listened constantly to his early idols: Charles Trenet, Tino Rossi, and Ray Ventura. He was said to love music above all else: it was his first passion and the path that led him to his career. He told his friend André Sève, "[It is] a kind of internal vibration, something intense, a pleasure that has something of the sensual to it." He hoped to enroll at a music conservatory, but his mother insisted that he could only do so if his grades improved. Consequently, he never learned to read music. A poor student, Brassens performed badly in school.

Alphonse Bonnafé, Brassens's ninth-grade teacher, strongly encouraged his apparent gift for poetry and creativity. Brassens had already been experimenting with songwriting and poetry. Bonnafé aided his attempts at poetry and pushed him to spend more time on his schoolwork, suggesting he begin to study classical poetry. Brassens developed an interest in verse and rhyme. By Brassens's admission, Bonnafé's influence on his work was enormous: "We were thugs, at fourteen, fifteen, and we started to like poets. That is quite a transformation. Thanks to this teacher, I opened my mind to something bigger. Later on, every time I wrote a song, I asked myself the question: would Bonnafé like it?" By this point, music had taken a slight backstage to poetry for Brassens, who now dreamed of being a writer.

Nonetheless, personal friendships and adolescence still defined Brassens in his teens. At age seventeen, he was implicated in crimes that would prove to be a turning point in his life. To get money, Georges and his gang started to steal from their families and others. Georges stole a ring and a bracelet from his sister. The police found and caught him, which caused a scandal. The young men were publicly characterized as "high school mobsters" or "scum" — voyous. Some of the perpetrators, unsupported by their families, spent time in prison. While Brassens's father was more forgiving and immediately picked up his son, Brassens was expelled from school. He decided to move to Paris in February 1940, following a short trial as an apprentice mason in his father's business after World War II had already broken out.

Wartime[edit]

Apprenticeships[edit]

Brassens lived with his aunt Antoinette in the 14th arrondissement of Paris, where he taught himself to play piano. He began working at a Renault car factory. In May 1940 the factory was bombed, and France was invaded by Germany. Brassens returned to the family home in Sète. He spent the summer in his home town, but soon returned to Paris, feeling that this was where his future lay. He did not work, since employment would serve only to profit the occupying enemy. Saddened by the lack of poetic culture, Brassens spent most of his days in the library. It was then that he set a pattern of rising at five in the morning, and going to bed at sunset – a pattern he maintained the greater part of his life. He meticulously studied the great masters: Villon, Baudelaire, Verlaine and Hugo. His approach to poetry was almost scientific. Reading, for instance, a poem by Verlaine, he dissected it image by image, attentive to the slightest change in rhythm, analyzing the rhymes and the way they alternated. He drew on this enormous literary culture as he wrote his first collection of poems, Des coups d'épée dans l'eau, the conclusion of which foreshadowed the anarchism of his future songs:

- Le siècle où nous vivons est un siècle pourri.

- Tout n'est que lâcheté, bassesse,

- Les plus grands assassins vont aux plus grandes messes

- Et sont des plus grands rois les plus grands favoris.

- Hommage de l'auteur à ceux qui l'ont compris,

- Et merde aux autres.

- The century we live in is a rotten century.

- Everything is but cowardice and baseness.

- The greatest murderers attend the highest Masses

- And are the greatest favourites of the greatest kings.

- Compliments from the author to those who understood this,

- And to hell with the others (shit to the others).

Brassens also published À la venvole in 1942, thanks to the money of his family and friends, and with the surprising help of a woman named Jeanne Planche, a neighbour of Antoinette, probably the first Brassens fan. Brassens later commented on his early works: "In those times, I was only regurgitating what I had learned reading the poets. I hadn't transformed it into honey yet."

Exile[edit]

In March 1943, Brassens was requisitioned for the STO (Service du travail obligatoire) forced labour organisation in Germany. He found time to write Bonhomme and Pauvre Martin, along with more than a hundred other songs, that were later either burned or frequently altered before they reached their final form (Le Mauvais sujet repenti). He also wrote the beginning of his first novel, Lalie Kakamou. In Germany, he met some of his best friends like Pierre Onténiente, whom he nicknamed "Gibraltar", because he was "firm as a rock." Onténiente later became his right-hand man and his private secretary.

A year after he arrived in Basdorf, Brassens was granted a ten-day furlough. It was obvious to him and his new friends that he wouldn't come back. In Paris, he had to find a hideout, but he knew very few people. Finally, Jeanne Planche came to his aid and offered to put him up as long as necessary. Jeanne lived with her husband Marcel in a hovel at 9 impasse Florimont, with no gas, water or electricity. Brassens accepted and stayed there for twenty-two years. He once said on the radio: "It was nice there, and I have gained since then quite an amazing sense of discomfort." According to Pierre Onténiente: "Jeanne had a crush on Georges, and Marcel knew nothing, as he started to get drunk at eight in the morning."

Anarchist influences[edit]

Once put up at Jeanne Planche's, Georges had to stay hidden for five months, waiting for the war to come to an end. He continued writing poems and songs. He composed using as his only instrument a small piece of furniture that he called "my drum" on which he beat out the rhythm. He resumed writing the novel he started in Basdorf, for only now did he consider a career as a famous novelist. The end of World War II and the freedom suddenly regained didn't change his habits much, except that he got his library card back and resumed studying poetry.

The end of the war meant the homecoming of the friends from Basdorf, with whom Brassens planned to create an anarchist-minded paper, Le Cri des Gueux (The villains' cry), which stopped after the first edition due to a lack of money. At the same time, he set up the "Prehistoric Party" with Emile Miramont (a friend from Sète nicknamed "Corne d'Auroch" – the horn of an Aurochs, an ancient large bovine species) and André Larue (whom he met in Basdorf), which advocated the return to a more modest way of life, but whose chief purpose was to ridicule the other political parties. After the failure of Le Cri des Gueux, Brassens joined the Anarchist Federation and wrote some virulent, black humour-tinged articles for Le Libertaire, the Federation's paper. But the extravagance of the future songwriter wasn't to everybody's taste, and he soon had to leave the Federation, albeit without resentment.

Brassens said in an interview: "An anarchist is a man who scrupulously crosses at the zebra crossing, because he hates to argue with the agents".[3] He also said: "I'm not very fond of the law. As Léautaud would say, I could do without laws [...] I think most people couldn't."

Career[edit]

His friends who heard and liked his songs urged him to go and try them out in a cabaret, café or concert hall. He was shy and had difficulty performing in front of people. At first, he wanted to sell his songs to well-known singers such as Les Frères Jacques. The owner of a cafe told him that his songs were not the type he was looking for. But at one point he met the singer Patachou in a very well-known cafe, Les Trois Baudets, and she brought him into the music scene. Several famous singers came into the music industry this way, including Jacques Brel and Léo Ferré. He later on made several appearances at the Paris Olympia under Bruno Coquatrix' management and at the Bobino music hall theater.

He toured with Pierre Louki, who wrote a book of recollections entitled Avec Brassens (éditions Christian Pirot, 1999, ISBN 2-86808-129-0). After 1952, Brassens rarely left France. A few trips to Belgium and Switzerland; a month in Canada (1961, recording issued on CD in 2011) and another in North Africa were his only trips outside France – except for his concerts in Wales in 1970 and 1973 (Cardiff).[4] His concert at Cardiff's Sherman Theatre in 1973 saw Jake Thackray — a great admirer of his work – open for him.[5]

Songs[edit]

Brassens accompanied himself on acoustic guitar. Most of the time the only other accompaniment came from his friend Pierre Nicolas with a double bass, and sometimes a second guitar (Barthélémy Rosso, Joël Favreau).

His songs often decry hypocrisy and self-righteousness in the conservative French society of the time, especially among the religious, the well-to-do, and those in law enforcement. The criticism is often indirect, focusing on the good deeds or innocence of others in contrast. His elegant use of florid language and dark humor, along with bouncy rhythms, often give a rather jocular feel to even the grimmest lyrics.

Some of his most famous songs include:

- "Les copains d'abord," about a boat of that name, and friendship, written for a movie Les copains (1964) directed by Yves Robert; (translated and covered by Asleep at the Wheel as "Friendship First" and by a Polish cover band Zespół Reprezentacyjny as "Kumple to grunt" and included on their 2007 eponymously titled CD).

- "Chanson pour l'Auvergnat," lauding those who take care of the downtrodden against the pettiness of the bourgeois and the harshness of law enforcement.

- "Brave Margot," about a young girl who gives a young kitten the breast, which attracts a large group of male onlookers.

- "La Cane de Jeanne," for Marcel and Jeanne Planche, who befriended and sheltered him and others.

- "La mauvaise réputation" – "the bad reputation" – a semi-autobiographical tune with its catchy lyric: "Mais les braves gens n'aiment pas que l'on suive une autre route qu'eux" (But the good folks don't like it if you take a different road than they do.) Pierre Pascal adapted part of the lyrics to Spanish under the title "La mala reputación",[6] which was later interpreted by Paco Ibañez.

- "Les amoureux des bancs publics" – about young lovers who kiss each other publicly and shock self-righteous people.

- "Pauvre Martin," the suffering of a poor peasant.

- "Le gorille" – tells, in a humorous fashion, of a gorilla with a large penis (and admired for this by ladies) who escapes his cage. Mistaking a robed judge for a woman, the beast forcefully sodomizes him. The song contrasts the wooden attitude that the judge had exhibited when sentencing a man to death by the guillotine with his cries for mercy when being assaulted by the gorilla. This song, considered pornographic, was banned for a while. The song's refrain (Gare au gori – i – i – i – ille, "beware the gorilla") is widely known; it was translated into English by Jake Thackray as Brother Gorilla, by Greek singer-songwriter Christos Thivaios as Ο Γορίλλας ("The Gorilla"), by Spanish songwriter Joaquín Carbonell as "El Gorila" ("The Gorilla"), by Italian songwriter Fabrizio De André as "Il Gorilla" ("The Gorilla" – De André included this translation into his 1968 album "Volume III"), by the Polish cover band Zespół Reprezentacyjny as "Goryl" and by Israeli writer Dan Almagor as "הגורילה".

- "Fernande" – a 'virile antiphon' about the women lonely men think about to inspire self-gratification (or to nip it in the bud). Its infamous refrain (Quand je pense à Fernande, je bande, je bande..., 'When I think about Fernande, I get hard') is still immediately recognized in France, and has essentially ended the use of several female first names.

- "Supplique pour être enterré à la plage de Sète" (in French), a long song (7:18) describing, in a colourful, "live" and poetic way, his wish to be buried on a particular sandy beach in his hometown, "Plage de la Corniche".

- "Mourir pour des idées," describing the recurring violence over ideas and an exhortation to be left in peace (translated into Italian by Italian singer-songwriter Fabrizio De André as "Morire per delle idee" and included in De André's 1974 album Canzoni and by the Polish cover band Zespół Reprezentacyjny as "Śmierć za idee" and included on their 2007 CD Kumple to grunt).

Death[edit]

Brassens died of cancer in 1981, in Saint-Gély-du-Fesc, having suffered health problems for many years, and rests at the Cimetière Le Py in Sète.

Legacy[edit]

Many artists from Japan, Israel, Russia, the United States (where there is a Georges Brassens fan club), Italy and Spain have made cover versions of Brassens's songs. His songs have been translated into 20 languages, including Esperanto.

Many singers have covered Georges Brassens' lyrics in other languages, for instance Pierre de Gaillande, who translates Brassens' songs and performs them in English, Luis Cilia in Portuguese, Koshiji Fubuki in Japanese, Fabrizio De André (in Italian), Alberto Patrucco (in Italian), and Nanni Svampa (in Italian and Milanese), Graeme Allwright and Jake Thackray (in English), Sam Alpha (in creole), Yossi Banai (in Hebrew), Arsen Dedić (in Croatian), Jiří Dědeček (in Czech), Mark Freidkin (in Russian), Loquillo, Joaquín Sabina, Paco Ibáñez, Javier Krahe, Joaquín Carbonell and Eduardo Peralta (in Spanish), Jacques Ivart (in esperanto), Franz Josef Degenhardt and Ralf Tauchmann (in German), Mani Matter in Bernese dialect, Zespół Reprezentacyjny (they released 2 CDs of Brassens' songs in Polish) and Piotr Machalica (in Polish), Cornelis Vreeswijk (Swedish) and Tuula Amberla (in Finnish). Dieter Kaiser, a Belgian-German singer who performs in public concerts with the French-German professional guitarist Stéphane Bazire under the name Stéphane & Didier has translated into German language and gathered in a brochure 19 Brassens songs. He also translated among others the poem "Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux" of the French contemporary poet Louis Aragon. Franco-Cameroonian singer Kristo Numpuby also released a cover-album with the original French lyrics but adapted the songs to various African rhythms.

An international association of Georges Brassens fans exists and there is also a fan club in Berlin-Basdorf which organizes a Brassens festival every year in September.

Brassens composed about 250 songs, of which 200 were recorded, the other 50 remaining unfinished.

Renée Claude, an important Québécois singer, dedicated a tribute-album to him, J'ai rendez-vous avec vous (1993).

Le Dîner de Cons, 1998's top-grossing film in France, used Brassens' song "Le Temps Ne Fait Rien a l'Affaire" as its opening title music.

His songs have a major influence on many French singers across several generations, including Maxime Le Forestier, Renaud, Bénabar and others.

In 2008, the English folk-singer Leon Rosselson included a tribute song to Brassens, entitled "The Ghost of Georges Brassens", on his album A Proper State.

The song "À Brassens" ("To Brassens") from Jean Ferrat's album Ferrat was dedicated to Brassens.

In 2014, Australian-French duo Mountain Men released a live tribute album Mountain Men chante Georges Brassens.[7]

"6587 Brassens" is an asteroid discovered in 1984 and named in honour of the French poet and songwriter.

Heritage sites[edit]

Many schools, theatres, parks, public gardens, and public places are dedicated to Georges Brassens and his work, including:

- L'Espace Brassens in his hometown of Sète, a museum to his life.

- A park built on the site of the former Vaugirard horse market & slaughterhouses, was named Parc Georges-Brassens. Brassens lived a large part of his life about hundred metres from the slaughterhouses, at 9, impasse Florimont and then at 42, rue Santos-Dumont. The park was inaugurated in 1975.

- A nearby station of Tram line 3 in Paris is also named in Brassens' honour.

- The Place du Marché of Brive-la-Gaillarde was renamed Place Georges-Brassens as a tribute to his well-known song Hécatombe, which name-drops the market.

- In the Paris Métro station Porte des Lilas (Line 11) there is a mural portrait of Brassens along with a quote from his song "Les Lilas", written for the 1957 film Porte des Lilas by René Clair. In this film, Brassens had a supporting role, practically playing himself.

Discography[edit]

All of Georges Brassens' studio albums are untitled. They are referred either as self-titled with a number, or by the title of the first song on the album, or by the most well-known song.

Studio albums[edit]

- 1952: La Mauvaise Réputation

- 1953: Le Vent (or Les Amoureux des bancs publics)

- including Pauvre Martin

- 1954: Les Sabots d'Hélène (or Chanson pour l'Auvergnat)

- 1956: Je me suis fait tout petit

- 1957: Oncle Archibald

- 1958: Le Pornographe

- 1960: Les Funérailles d'antan (or Le Mécréant)

- 1961: Le Temps ne fait rien à l'affaire

- 1962: Les Trompettes de la renommée

- 1964: Les Copains d'abord

- 1966: Supplique pour être enterré à la plage de Sète

- 1969: Misogynie à part (or La Religieuse)

- 1972: Fernande

- 1976: Trompe la mort (or Nouvelles chansons)

- 1979: Brassens-Moustache jouent Brassens en jazz (with Moustache and les Petits français, jazz versions of previously released songs; re-released in 1989 as Giants of Jazz Play Brassens)

- 1982: Georges Brassens chante les chansons de sa jeunesse (cover album of old songs)

Live albums[edit]

- 1973: Georges Brassens in Great Britain

- 1996: Georges Brassens au TNP (recorded in 1966)

- 2001: Georges Brassens à la Villa d'Este (recorded in 1953)

- 2001: Bobino 64

- 2006: Concerts de 1959 à 1976 (box set featuring concerts from 1960, 1969, 1970, 1973 and 1976)

References[edit]

- ^ Bernard Lonjon (20 September 2017). Brassens, les jolies fleurs et les peaux de vache [Brassens, pretty flowers and cowhides] (in French). Archipel. ISBN 978-2-8098-2298-4.

- ^ Mura, Gianni (13 March 2011). "Brassens, il burbero maestro di tutti i cantautori". repubblica.it. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ "Un anarchiste est un homme qui traverse scrupuleusement entre [...] - Georges Brassens". Dicocitations (Le Monde) (in French). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Georges Brassens – La marguerite et le chrysanthème. Pierre Berruer. Les Presses de la Cité, 1981. ISBN 2-7242-1229-0

- ^ Allen, Jeremy. "Cult heroes: Jake Thackray was the great chansonnier who happened to be English: He was a staple of light entertainment TV shows in the late 60s, but there was a clever and despairing comedy underlying Thackray's songwriting," The Guardian (15 September 2015).

- ^ "La mauvaise réputation & La mala reputación - Georges Brassens - Les Caves du Majestic". cavesdumajestic.canalblog.com (in French). 30 May 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ Mountain Men Chante Georges Brassens

External links[edit]

Media related to Georges Brassens at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Georges Brassens at Wikimedia Commons- (in English) Espace Brassens museum in Sète Archived 30 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- (in French) Georges-Brassens.com

- Georges Brassens at IMDb

- (in English) Georges Brassens Page from the Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia

- (in English) Project Brassens Brassens's complete production with English and Italian translations. Toutes les chansons de Georges Brassens avec les traductions des textes en anglais et italien - Tutte le canzoni di Georges Brassens con i testi tradotti in inglese e italiano.

- 1921 births

- 1981 deaths

- People from Sète

- French male guitarists

- French male singer-songwriters

- French people of Italian descent

- French anarchists

- French satirists

- 20th-century French poets

- Members of the French Anarchist Federation

- 20th-century guitarists

- 20th-century French male singers

- French World War II forced labourers

Comments

Post a Comment